For most of 2023, my bedroom window looked out onto a 30-foot-tall, blue-gray mural of the heroic Ghost of Kyiv. Word of the flying ace’s exploits spread like wildfire in the days after Russia’s late February 2022 invasion. He was said to have downed six Russian aircraft as enemy forces attempted to take the capital.

The Ghost’s legend grew for another couple months before Ukraine’s air force admitted they’d created him as a “superhero-legend.” Even so, the resilience and hope he represented lives on through the country’s nearly ubiquitous and often thrilling street art.

Kyiv is a city of murals, with more than 150 in all. Most began appearing after the Euromaidan protests of 2013-2014, which led to the collapse of the Russia-aligned government. Since then, Ukrainians have weathered the annexation of the Crimean peninsula, a decade of war in the country’s east and a full-scale invasion, and the number of murals has steadily increased.

Mostly commissioned by local arts groups, artists from all over the world—from Argentina to Australia—have turned their talents to Kyiv’s walls, often combining elements of Ukrainian folk art into their works. They are a powerful testament to the city’s strength, a reminder that even in the darkest times, creativity can flourish.

The older murals often depict fairy tales, musicians and activists, but since early 2022, street art in Kyiv and beyond has mainly honored soldiers and the broader war effort. Well-known symbols of heroism and resistance include Patron, a mine-detecting Jack Russel terrier and the mascot for Ukraine’s emergency services, and Oleksiy Movchan, a volunteer fighter who helped rescue 11 civilians and a cat before being killed by Russian shelling.

One of Kyiv’s older works of public art is a 2015 portrait of Serhiy Nigoyan, thought to be the first person shot dead in the Euromaidan protests, by Portuguese artist Alexandre Farto (known as Vhils). It stands on a building near St. Michael’s Square, overlooking a garden dedicated to those killed in the protests, often referred to as the “Heavenly Hundred,” as that’s roughly how many protesters perished.

The nearby St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery opened its doors to protesters during Euromaidan, protecting them from riot police and becoming a field hospital for treating the injured amid violent clashes. Nigoyan’s face now watches over it like a guardian, a constant reminder of the seemingly endless struggle against Moscow. First built in the Middle Ages, much of the monastery was destroyed by Soviet authorities in the 1930s before being rebuilt after Ukraine gained independence in 1991. An activist told local media at the time that they chose Farto because his work “comes through destroying in order to create.”

Amid the uncertainty of war, art has gained profound significance: a conduit for processing trauma, a reflection on the collective experience, and a means of expressing complex emotions that are often difficult to articulate, including fear, anxiety, and grief. Combining it with the urban scenery turns the city into a living story, an open-air gallery that enables residents to confront their feelings and publicly take part in the national struggle.

Art doesn’t just help people heal, it’s also a vital act of defiance and resistance. These creative works help establish a visual language and a national identity. Art emblazoned across an urban landscape still heavily defined by Soviet design is an act of reclamation. Each mural tells a story, and together they create a uniquely Ukrainian tapestry of history and contemporary life.

“Since the Maidan revolution, we’ve had a huge boom in arts and crafts that we didn’t even know existed here,” said Katya Taylor, a Ukrainian art curator and founder of Port.agency, a cultural development platform. “We had a lot of influence from Moscow and then the government rejected Russian music, cinema, and money, so there was a space and we started to fill it ourselves.”

Taylor was recently appointed to a new city commission that will vet and review all new mural proposals. The commission is developing a process to ensure that future works adhere to high artistic and moral standards, while preserving the look of historic districts. The new body underscores how creativity and public expression have accelerated since the full-scale invasion.

These days, engaging in local culture is a way to show patriotism and unity. “Culture is the basis for identity,” said Taylor. “People didn’t think about it before. Now the sector is booming—people need it in a sort of therapeutic way. You can’t even get tickets for the theatre.”

Kyiv is a lovely city, with lush parks lining the Dnipro river, but the almost austere mix of Soviet, Modernist, and Brutalist architecture is not for everyone.

Kyiv is a lovely city, with lush parks lining the Dnipro river, but the almost austere mix of Soviet, Modernist, and Brutalist architecture is not for everyone. Perhaps the greatest charm of the city’s murals is that they bring a pop of personality and color to a landscape that can at times feel grey and gloomy. This is particularly welcome in the drab winter months, when Ukraine is all but entombed in a harsh, snowy darkness.

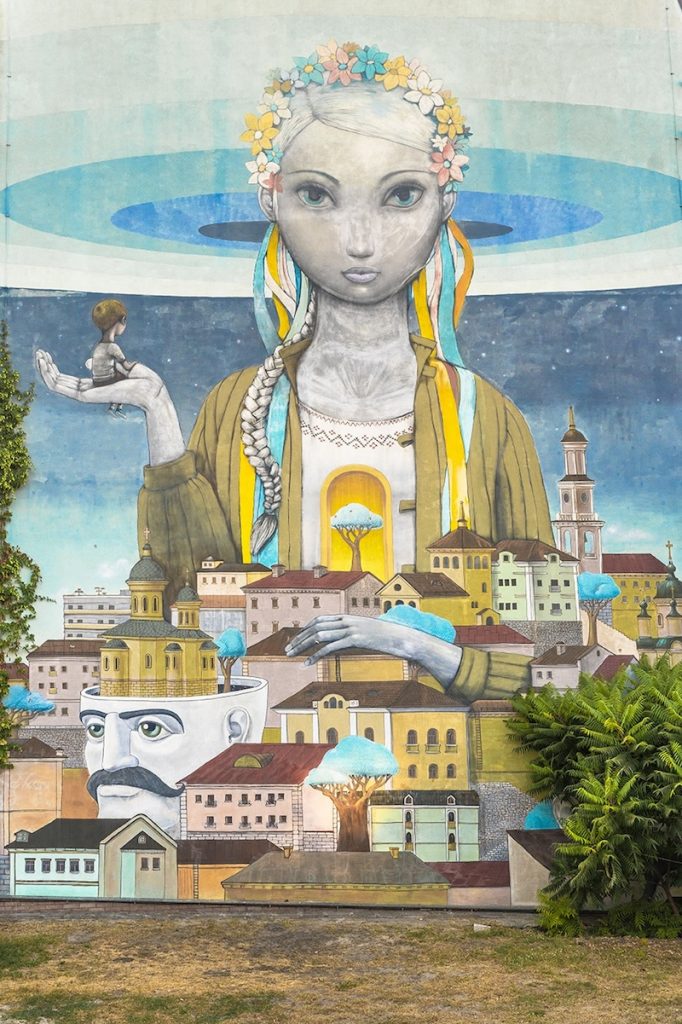

Looming over the serpentine Andriyivskyy Descent is perhaps Kyiv’s best-known mural, and one of its oldest. “Revival,” by Ukrainian artist Aleksey Kislow, appeared on the side of a five-story residence a few months after the early 2014 revolution. The serene, almost zen scene is said to show a new Ukraine, embodied in the face of a young girl wearing a military jacket and protecting the homeland. Fittingly, the pinks and reds of her ribbons have faded over the years, making the girl look more and more patriotic as the blues and yellow stand out.

Other well-loved works include a portrait of a girl engulfed in sunflowers, a symbol of Ukraine, and “Freedom” by Ukrainian Alex Maksiov, which shows a bird looking through an electric light bulb at a trapped humanity. “Red Bicycle,” by Canadian artist Emmanuel Jarus, transforms a velodrome in central Kyiv with a giant, hyper-realistic self portrait, encouraging viewers to pick up a bike. A mural of a war-time internet meme, Saint Javelin, looms over a street in the Solomianskyi district. The iconic image of a religious icon cradling a U.S. Javelin anti-tank weapon was created in 2012 by former journalist Christian Borys. Since the start of the full-scale conflict, it has come to symbolize Ukraine’s fight and the support of international allies, raising millions of dollars for the war effort through merchandise.

Perhaps the most famous international works are by the British artist Banksy, which appeared in bombed-out areas of Kyiv, as well as Borodyanka and Irpin, in mid-2022, not long after the Kyiv region was liberated from occupation. One shows a child judoka throwing an adult to the ground and is often interpreted as representing Ukraine’s David-and-Goliath struggle against Russia. The works sparked global headlines when they first appeared, yet within months one had been stolen and the others were put under police protection.

Art has a long and broad history of turning the scars of war into something rich and beautiful.

Art has a long and broad history of turning the scars of war into something rich and beautiful. The horrors of the Spanish Civil War prompted Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, perhaps the best-known conflict-inspired work. The Berlin Wall, once a global symbol of division, is now a lengthy open-air gallery featuring more than 100 murals by artists from around the world. Similarly, in Gaza, where locals have been hemmed in by border walls for decades, street artists have taken to using those walls as their canvas.

Though Kyiv is hundreds of miles from the front lines and protected by advanced air defenses, it still suffers regular missile and drone attacks. Some parts of the city bear physical marks of the war—shattered buildings, statues cloaked in sandbags, military checkpoints, and anti-tank obstacles known as Czech hedgehogs are scattered across the streets. Still, art softens the edges and takes the bite out of an otherwise intimidating atmosphere. Activists frequently stage events next to public works, painting Czech hedgehogs with traditional floral designs or showcasing sculptures that turn elements of war into emblems of Ukrainian pride.

There may be no better evidence of the power of Ukraine’s public art than the fact that its foe has shown a compulsion to remove them. One famous mural on the side of a residential block in Mariupol, part of a complex I briefly lived in just prior to the invasion, showed a young girl, Milana, clutching her teddy bear. She had lost her mother and a leg to shelling in 2015. The painting became a symbol of the war next to Freedom Square, which was surrounded by an artwork advocating peace—traditional embroidery on the wings of 25 doves, representing Ukraine’s regions. After Russian forces took the city in mid-2022, the mural was painted over, the birds were removed and the square was renamed for Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin.

Similarly, the Ghost mural has become a local landmark in Kyiv’s Podil neighborhood, known for its historic architecture and young hipsters. With its striking visual similarities to the rebel pilots in Star Wars, the mural was for me a reassuring vision whenever the air raid sirens wailed or drones and missiles descended in the middle of the night. The Ghost provided much-needed company when the capital’s air defenses spat orange tracer fire across the sky and when explosions shook me out of bed. Thumb up, visor down, fighter jet zooming past in the distance, the Ghost seems to send a message to passersby: “I can take on anything—and win.”

War is a time of transformation as well as destruction. Right now, Ukraine is discovering its power through its extraordinary resilience. Just as the artist Farto destroys in order to create, creative expression is part of that shift. As the nation evolves, so too will the visual landscape of its cities, especially those that now lie in rubble.

———————

Based in Istanbul and Kyiv, Liz Cookman is an award-winning British journalist who writes about the impact of war for The Economist 1843, The Guardian, Foreign Policy, The Sunday Times and other top outlets. Find her on X.

Liz Cookman