I swear that big bull had me in his sights. Horns squared, nostrils flared, he was headed straight for me, and not taking his time about it. For an unbearably long half-second on the morning of Friday the 13th in Pamplona, Spain, I wondered if I’d see my wife and kids again.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The journey that put me in the crosshairs of a large and surprisingly fast bovine began the summer before, when a small group of us, including Joel Nagel, Kathie Peddicord, and Leif Simon, met to watch the iconic Palio de Siena.

The rules are simple: be 18 or older, run in the same direction as the bulls, do not tease or incite the bulls, and be sober.

The thundering horse race around the medieval central square of Siena, in Italy’s Tuscany region, had been on my bucket list at least since I watched my now-teen daughter Amanda chase pigeons around a park as a toddler. The Palio was exhilarating and frantic and I was delighted to cross it off the list—and write about it for Escape Artist.

In Siena, Kathie mentioned that she was a huge Ernest Hemingway fan and had always wanted to go to Pamplona for the running of the bulls. His 1926 novel, The Sun Also Rises, is mainly about bullfighting and the city’s San Fermin Festival. This being Hemingway, it’s also about fishing and getting drunk. Anyway, at Kathie’s urging we agreed to meet in Pamplona the following summer for the running.

I’m not sure why, but I soon got it in my head that I would take part in the run. Just seemed like the “Mike” thing to do. About a month before the event, I started psyching myself up and doing research to prepare myself to tangle with massive, hard-charging bulls. I knew almost nothing about it, and what I found was fascinating.

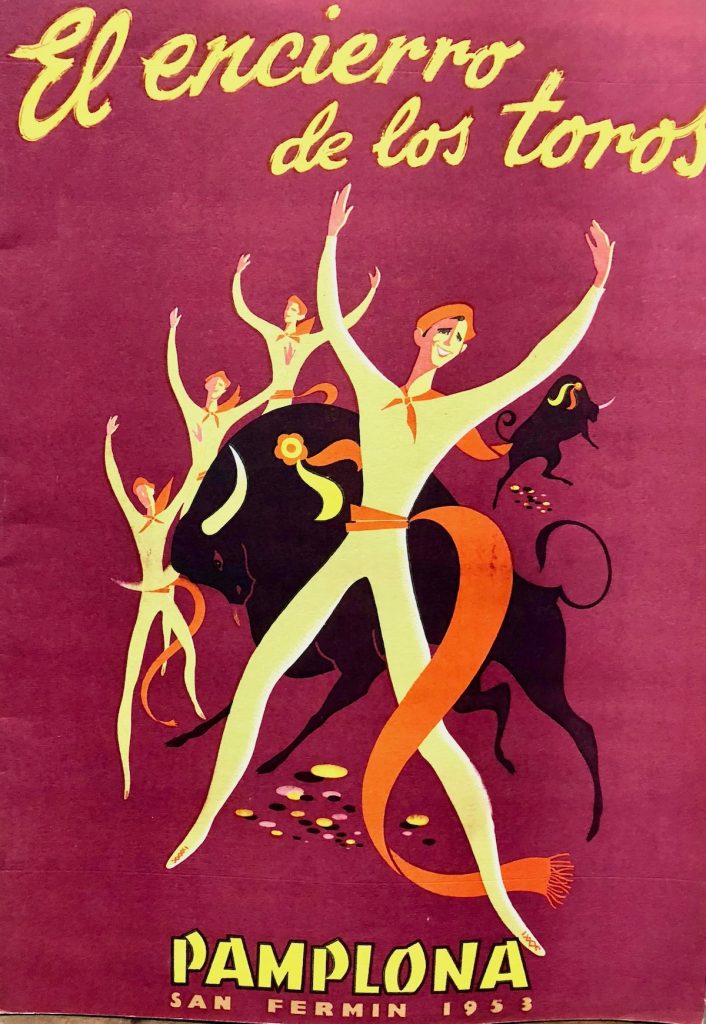

The event goes back 700 years, and originated in local ranchers’ practice of leading bulls from the fields outside town to the bullring in the city center where they’d fight later that day. During this bull “run”, or encierro, bold young locals started jumping on bulls or jogging next to them, and a tradition was born. With the publication of The Sun Also Rises a century ago, the Pamplona event became the world’s best-known bullrun, attracting thrill-seekers from around the globe.

Today, Pamplona holds a run every morning of San Fermin, from July 7-14. Each run involves six bulls and six steers, or about 15,000 pounds of angry beast. The rules are simple: be 18 or older, run in the same direction as the bulls, do not tease or incite the bulls, and be sober. Also, no cameras—and that includes smartphones and GoPros. I’m guessing they had a few too many younger runners knocked sideways while pausing for a danger selfie.

All reasonable guidelines, but what I really wanted to know was will I be trampled to death? I watched countless YouTube videos of actual Pamplona bull runs and learned that the most dangerous spot on the half-mile course is the sharp bend at Calle de Cuna. To locals it’s “La Curva.” Foreigners take a more glass-half-empty approach, calling it “Deadman’s Curve” because it’s often where bulls mash runners up against the wall.

I can’t say watching the videos helped. Each trampling frayed my nerves a bit more. Every year 50-100 participants are injured, a handful of them seriously. Death by goring, I finally learned, is exceedingly rare. The last happened in 2009. So, the odds were on my side, in terms of staying alive. They were also pretty good for avoiding injury, if you consider the 3000-plus participants over eight bull runs. I started to feel a little better. A little.

The biggest threat is not the bulls, it turns out, but other fleeing humans. Every year, most injuries come from people running up other participants’ backs while looking around for the bulls. Duly noted, but I’ll still be keeping an eye out for half-ton bulls.

Taking a train from Barcelona, I arrived on the afternoon of the 12th and soon met my three fellow runners and our four-person support group. Pamplona is set in the Pyrenees’ foothills and we enjoyed a fantastic “last supper” at El Buho Restaurante, with incredible views from the rooftop. The calamari was outstanding, and we were able to watch “our bulls” being led to the San Fermin corral in preparation for the next morning’s run. They looked ornery.

After a post-dinner stroll through old town, I returned to my hotel—the Maisonnave, a great place to stay in the center—and went to bed. Sleep took its time coming. My stomach churned as I stared at the ceiling, doing my best not to think of bull horns. Somehow, I awoke at 5:30 the morning of Friday the 13th feeling rested and excited.

I also felt anxious, but not about the bulls. I feared I wouldn’t be able to find a coffee at this early hour in late-rising Spain. Thankfully, the front desk clerk took pity on me and made me a fine café Americano. He probably thought this crazy American deserves one last coffee before he gets skewered by a bounding steer. While waiting for the coffee I glanced at a nearby newspaper, which just happened to show a man being steamrolled by a bull. The nerves returned.

Our group met in the lobby and walked out into the pre-dawn gray, following the cobblestone streets to the spot on the course I’d chosen after meticulous safety research. The run has four main sections: the uphill opening sprint on Calle de Santo Domingo; a brief stretch on Mercaderes leading into the terrors of La Curva; the long straightaway on Calle de la Estafeta; and finally Callejon, leading to the bullring entrance.

The biggest threat is not the bulls, it turns out, but other fleeing humans. Every year, most injuries come from people running up other participants’ backs while looking around for the bulls.

I was 53 at the time and rarely jogged, cross-trained, or did any kind of cardio, so I knew I wouldn’t be able to run a half-mile at full speed, or even semi-full speed. That meant the opening sprint was out. So was Deadman’s Curve, for obvious reasons. At Callejon, the street narrows leading into the bullring, which results in bottlenecks and tramplings, so we settled on Estafeta.

But where’s the safest spot? There may not be one. “The danger tends to increase in Estafeta as very often there is a bull that gets separated from the pack when it has slipped up at Deadman’s Curve,” says one San Fermin advice website. “It’s almost impossible to run the length of Estafeta as the bulls will overtake you and you’ll need to find a moment to get out of their way.”

From my YouTube research I learned that the bulls’ momentum at La Curva usually carries them to the far side of Estafeta, the eastern side, for the start of that straightaway. So, I chose the western side of the start of Estafeta as the spot most likely to ensure our survival. I felt confident I could run the quarter-mile from there to the end, especially with the added motivation of 12 goring and trampling machines at my heels.

Walking to the bullrun, a Toby Keith lyric floated in my head: “I ain’t as good as I once was, but I’m as good once as I ever was.” I’d run like the wind for as much of Estafeta as I could, then step aside and let the bulls rumble past. Piece of cake.

We arrived early to secure our place and waited as daylight arrived. We talked nervously about what to expect, but we didn’t really know. It hadn’t hit me yet, what I was doing here. Somehow it still didn’t feel real. Only a few other runners were around at that early hour, but still the 18-foot-wide alley felt narrow. Imagining myself running alongside a friend as two Volkswagen-sized bulls surged past us, it seemed a bit too close for comfort.

Hearing our English, a thirty-something man introduced himself as Antonio, an ESL teacher from California. His uncle lives in Spain and he was visiting for the summer and decided to run. There by himself, and also a newbie, we added him to our merry band, and were stunned to find he was wearing a wristband from one of our favorite Belize beach bars.

A worker came by to string up the festival’s official video and photo equipment. They rely on the same high-line cameras used at NFL games, only here they run along the entire length of the course. This official filming is an absolute necessity and must be done well because of the ban on cameras. We know this because around 6:30 am we were herded back to Plaza Santo Domingo, near the starting area, to watch the rules of the race on a giant video screen.

We were reminded again of the no camera and no phones rule, as well as no backpacks, bags, bottles, or packages of any kind. We were also advised that if we fell down we should stay down. Laying on the ground in front of a wave of marauding bulls sounds like a recipe for disaster, but they say that gorings generally happen as people try to get back on their feet. On the ground other runners might trample you, but bulls rarely do, so apparently lying low is the way to go.

I feel a surge of nerves and adrenaline and look up to see a wave of bodies rushing around the curve some 30 meters away.

After a quick frisking to ensure we’d handed off our devices, we returned to our spot on Estafeta to wait for the exploding rocket that signaled the bulls’ release from their corral. Suddenly, it’s all very real as the seconds tick down to 8 am. There’s no way out of this now, Michael, you’ve gone and done it this time – prepare yourself for the perils of the gauntlet.

Boom! The rocket reports and the bulls are on the course. I feel a surge of nerves and adrenaline and look up to see a wave of bodies rushing around the curve some 30 meters away. And then I see why.

Four snarling bulls come banging around La Curva, and that’s when I locked eyes with one of them. Or at least I thought I did. For the briefest moment I could’ve sworn he was staring me down. I turned and dashed up the alley—and banged smack into somebody’s back.

Regaining my balance I continued jogging up Estafeta. I kept my eyes forward, my back to the charging bulls, as we had been urged to do. Tripping over people causes many more injuries than bulls, they tell us. OK, I believe you, but I bet it hurts a lot more when it’s the bull delivering the blow.

Where had my group gone? I don’t see any of them, but I do hear cow bells and two seconds later the first group of four bulls bounds past in a blur. The pace picks up and I’m running full speed now. More cow bells and two more bulls appear a few feet to my left.

We’re running at about the same pace and for a moment I almost want to reach out and touch them. But then they disappear into the mass of bodies and swirling madness and I find myself entering the bullring. My run with the bulls felt like both an eternity and a split-second. In reality it lasted nearly a minute, and what a glorious minute it was.

I find my friends for a laugh and an embrace before climbing over the ring enclosure to watch the spectacle of bulls charging participants who haven’t had their fill of danger. One of the thrill-seekers flees a huge steer in my direction and when he dives over the wall to save himself his foot catches me smack in the face—a little reminder that this has been a very real morning.

Back at the hotel for a well-earned buffet breakfast, we shared our tales of running with the bulls. Apparently we were all separated immediately. One of us was nearly trampled. Somebody said they weren’t as scared as they thought they’d be. I smiled, sipping one coffee after another, happy to be alive.

—————

Michael K. Cobb is the CEO and Co-founder of ECI Developments, which has properties throughout Latin America. He is the author of How to Buy Your Home Overseas, and speaks all over the world on international real estate.

Michael K. Cobb