On our first morning in Palermo, Savannah and I found a grassy area beside Teatro Garibaldi where we could stand in the sunlight to wake up. Birds whistled from the wires, stilettos tapped the cobblestone, and children made circles on their bikes. The peace of the place washed over me—until a pair of shutters clanged open and a woman shouted. “Luigi!”

I spun around to see a woman slapping her hands together and a man jogging across the square. The man spoke to the woman from below her third-story window, then the woman lowered a plastic bucket to him, he took some coins from it, and the woman reeled the bucket back up. In all likelihood, Luigi was fetching something ordinary like bread or a newspaper, but the scene felt like a dream. I had no idea there were people named Luigi outside of video games or that a woman could call from her third-story window with such flair.

Read more on The Less Traveled Path

Up the Italian Coast

After Palermo, I stopped to people-watch, linger by the sea, and sip cappuccinos at every opportunity. Italy’s grandeur was too much for me. In most countries, even though I was a gangly white man pushing a baby carriage and walking a dog, I didn’t feel out of place.

There were always blue-collar workers in clothes as stained as mine, but as I made my way up Calabria, then Campania, I never felt more uncivilized. While women dressed neat as a pin and men strolled to work in tailored suits, I wore the same sun-bleached outfit and the same torn sneakers that saw me across Algeria and Tunisia. Certainly I smelled, too.

But my lack of refinement was a secondary anxiety compared to the fact that I was turning thirty. Typically, I didn’t acknowledge my birthday, but I felt my thirtieth looming. Even though I was living my dream, I couldn’t help but feel I was behind in life. While my friends had careers and homes, I was earning twenty thousand dollars a year and living out of a tent.

What Am I Doing Here

My anxiety reached its peak the day before my birthday. Savannah and I were in Tuscany, following a hilltop road where on either side of us green valleys and hills rolled in small swells to the plains in the north. It was a stunning setting, but the only thing I could think of were the ways I failed and the lives I hadn’t lived.

My life with Layla had failed; I should have been with her in Colorado, skiing on the weekend and raising a family. My schooling had failed; my psychology degree was useless until I obtained a doctorate. And worst of all, I had failed my family. I should have been in Philadelphia with my parents, my sister, and my grandparents, but instead I was called to satisfy some amorphous and selfish desire to be out there.

At night, I camped in a shallow depression and read Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations:

To bear in mind constantly that all of this has happened before. And will happen again—the same plot from beginning to end, the identical staging.

Blessed Birthday

When I woke on my thirtieth, I discovered my anxiety had lifted in the night. I remembered that I had chosen the life I was living—I was in Tuscany, and I had brought myself there with my own two feet. To the east, billowy clouds were made a fiery red by the burning sun behind them.

The clouds tumbled from the mountains and splashed into a dense fog that settled over the valley and rose to my toes. Rainbows appeared and vanished like the crests of breaking waves. Soon the clouds were so thick that the distant mountains and the narrow road were the only solid things I could see. For half an hour, I watched the most beautiful sunrise I’ve ever seen.

Down the road, in San Quirico d’Orcia, the room I reserved was in a cramped but ornate hotel.

“Your reservation is for a small room, Mr. Thomas.” “That’s okay, it’s just for a night.”

“We have a new building on the other side of town. It’s the same hotel, just newer, we opened it a year ago. If you’d like, we can upgrade you to a bigger room free of charge.”

“The new hotel is in town?” “Oh yes, down the street.”

“And I won’t be charged for the upgrade?”

“No. The room you reserved would be tight for you and your things, you see?”

Savannah and I found the new hotel on the other end of town and were shown to a suite that was entirely white, but with a king bed and a deep tub. After a bath, I sat around for an hour then walked to the center by way of cobblestone streets between pastel houses. I thought every part of Tuscany was busy year-round, but other than a couple of honeymooners, I was the only tourist I’d seen.

Eating, Drinking, Camping Out

For dinner, I ate at a restaurant in a cellar. I had four spinach and ricotta ravioli and a glass of house red, then I ambled to the piazza beside the gardens and took a seat beneath the green awning of Bar Centrale. “Something local,” I said.

The waiter poured me a splash of Tuscan wine. I drank one glass after another until I was good and drunk. A handful of people were imbibing inside, a soccer match was on, but I was the only person in the piazza. I watched a few locals walk home and listened to a man humming as he went. Around ten, I stumbled back to the hotel playing Dean Martin on my phone.

I barely had an income, just enough for food and the occasional room, but I possessed time in abundance and most days that was a wealth beyond dreams. I never enjoyed sleeping on someone else’s land, but some nights I had little choice.

A week later, under the pale light of a crescent moon, I turned from the road and into an olive grove. The trees were old and the branches were clipped to form a wide canopy. To the north the trees carried into the dark, but to the west was a highway and I could hear its thrum.

On the grass beside the fence that separated the olive grove and the street, I set my tent. For dinner, I ate another heavenly meal of fresh casarecce and ragu cooked on my stove. Once I finished, I used my finger to clean the side of my pot. Savannah came over for her nightly dental chew then ran with it to the base of the nearest tree.

Night Visitor

As I watched her eat, I heard a distant grunt from somewhere in the grove. I went to Savannah and stared into the grove and listened. I could see as far as twenty trees, but beyond that, the world was dim. After five minutes of no sound, Savannah and I returned to camp and went to sleep. In the night, I woke with a jolt of adrenaline.

Savannah was growling at something huffing outside. I found my knife, held Savannah’s collar to keep her from charging, then unzipped the tent. Five feet away, backlit by the moon, was a massive, hairy, blade-tusked boar. The boar didn’t move to acknowledge us, but it huffed low and then high like it was whining.

If it decided to charge into the tent, there was nothing Savannah and I could do to escape. I couldn’t reach my cart to block it, and my four-inch knife might not even break its thick hide. Over my months of walking in Europe, I had become adept at avoiding where boars slept. In France, after waking in a field surrounded by two hundred boars that scattered the moment I opened my tent, I learned how they tilled the land to make their bed and I never forgot it.

After that, there were occasions when I walked away from an otherwise good campsite because I recognized the familiar pattern in the earth. But I had seen no sign of boars in the olive grove, and this was the only time I’d seen a single boar on its own. They always gathered in sounders.

The boar turned its head. Its tusk was stained and curled. Its small eyes were a glint. I pulled Savannah closer because the boar seemed ready to charge, but instead it squealed and shot away from us into the darkness. I stepped outside and swept the light of my headlamp over the grove. Savannah stood tall beside me. I could see no other boars. “Good job, baby girl.”

Reunion in Croatia

Savannah stood on her hind legs to look over the balcony. I could hear my dad’s voice echoing through the walled city but I couldn’t yet see him. “Savannah!” he called musically. Savannah yipped, then began barking and wouldn’t quit. She turned to me, then peered over the balcony again.

When my parents and Lexi finally came into view, I went to the stairwell and jogged down with Savannah to the patio entrance. I opened the door and Savannah ran to the only people that she’d lived with for longer than a month other than me.

She jumped and squirmed between their legs. She whined and bounced and rolled over to paw the air. I hugged everyone between the moments they weren’t showering Savannah with affection.

“Welcome to the motherland,” I said. “Are you hungry? Did you eat?”

“Checked into our rooms and came straight over.”

“Perfect. I’m sure we can find somewhere that’s still open.”

We walked a few minutes through the narrow Zadar alleyways until we found a restaurant with a wooden table outside. The owner said they were closing, but that he would stay to serve us. Savannah sat beneath the table and poked her head through everyone’s legs.

We ordered calamari, monkfish, white fish, and a bottle of Plavac Mali. Lexi told us about moving to Denver and how she was glad to escape the small resentments that had built up over the years between her and her friends. I caught my family up on everything that had happened since I last saw them, and how our cousins on the island Krk were excited to meet them.

The Family from Krk Visits Krk

My dad couldn’t wait. For most of his life, it was his dream to see his grandfather’s home and the island we came from. After two nights in Zadar, we drove to Krk. For me, it was backtracking, I’d stayed on Krk for a month with Ernest and Margaret, family who had a home near the center of the island. Over that month I met every cousin in the area but spent most of my time with Smiljana, Edi, and their girls, Ema and Andrea.

Smiljana and Edi lived in Rijeka, the city across the water. On Krk, my dad woke early to take a walk and see as much of the island as possible before everyone else was awake. Once he found a guidebook about the stonework on Krk, he started pointing out what he learned when we were out exploring. “The holes on the second story were for curing sausage too high to steal.”

His favorite moment, other than visiting family, was when we stumbled across a fourth-century church during a walk in the woods. “The fourth century!” he kept saying. “Sitting in the middle of the forest like it’s nothing.”

So Many of Us

One afternoon, Smiljana told us there was a cemetery where most of the Turcich relatives were buried so we made our way to it by following a back road on the west side of the island. It took us a long time to find the place, but eventually, at the end of a dirt lane, we came to a stone church with a bell tower high above the trees.

Behind the church were a hundred burial plots bordered by an iron fence. The plots were familial and the headstones were marked by black- and-white portraits. There was Maračić, Žgombić, Bogović, and on about a third of the headstones was Turčić. “Crazy,” my dad said in a low voice.

My parents and Lexi made a slow lap around the cemetery then went to the steps out front to rest in the shade. I lingered a little longer, crouching before a headstone with a hand on the raised bed where weeds burst through the soil. I couldn’t take my eyes off the name.

In Ireland, I wasn’t capable of fully appreciating my connection to the place. Although I visited my great-grandfather Andrew’s home and stayed with relatives across the island, the place was too alive for me to feel my ancestral roots. But now, gazing upon the name Turčić carved in stone, it was as though everything I’d been told about my family was verified.

We’re Water People and Farmers

My ancestors were real. I had come from this island. The next day, we met cousins at a restaurant in Dobrinj—a hilltop village with views of the Adriatic. Smiljana, Edi, and the girls were there, as were Uncle Ivica, Aunt Katica, and cousins Ivana, Lucija, Igor, Mia, and Dora. We occupied two tables aside the piazza.

Zora was one of the few restaurants that made traditional šurlice, a Krk pasta tediously crafted by coiling each piece of dough around a wooden stick then dousing the finished pasta in a beef goulash.

“What do you think of your motherland?” Smiljana asked my dad. “It explains why we were raised on a river and why my dad was in the Coast Guard.” From lunch we drove to Gostinjac, the village beside Dobrinj, where my great-aunt Dusica and her husband lived. Dusica had a garden that wrapped around her house, and in the back, she had a small farm with corn and chickens.

“She’s the toughest woman you’ll meet,” Smiljana told me as we approached. “She runs the whole place by herself. She used to have goats, chickens, potatoes, and just about everything else, but Nikola fell sick and taking care of him has taken up most of her time. Nikola was strong in his day, but he’s almost ninety.”

The cousins descended on Dusica’s home like a swarm. In her basement, Dusica pointed to the bottles of homemade rakija and the hocks of prosciutto she’d hung to cure. I took a swig from one of the wicker-covered bottles and thought I ingested gasoline. Lexi was in tears with laughter.

Stepping Back in Time

“Why would she keep gasoline in there?” she said. “I don’t know, but that can’t be drinkable.” After showing us her home, Dusica led us across the street and down a narrow stone-walled lane. At a bend, we came to the gate entrance of two stone houses.

“Your great-grandfather Anthony’s home,” said Smiljana. “The one further away. The family used to own the land, but it’s not ours anymore. Someone remodeled it recently.”

We took the lane a little further and it tightened between the walls until we stopped at another stone house that was only three walls and a caved-in roof. A mound of stones was set beside the house as though the missing wall had been dismantled piece by piece.

“This was your great-great-grandfather’s home.” I couldn’t see much of it because the bushes were so overgrown. “Gives you an appreciation for your ancestors, doesn’t it?” said my dad. “How anyone managed to live here, I don’t know.” “It’s no wonder they came to America.”

“And on the back of a pamphlet. We wouldn’t be here if they hadn’t.”At that moment, I wondered if my need for adventure came from my dad, or if it had been in our blood for generations. Maybe Anthony and his brothers didn’t leave Krk because it was a barren island of stone and a pamphlet promised more in America; maybe they left simply for the adventure of leaving.

Sunset on the Adriatic

Maybe we had both left in order to satisfy that innate need to reach into the unknown. Whatever the motivation, Anthony was successful. He made it to America. He built a life in Philadelphia and his progeny multiplied into the hundreds.

After a week on Krk, my parents and Lexi returned Savannah and me to Zadar. On our final afternoon together, we hired a boat to take us onto the water to watch the sunset. Alfred Hitchcock called Zadar’s sunset the best in the world. When we came to a stop, I jumped off the side and swam out.

When I was far enough away, I looked back to the boat. My dad was talking to the captain, Savannah was watching me from the stern, my mom and sister were chatting on the bow. The sunset was nearly green in the haze. I thought of my great-grandfather, Anthony— how by leaving Croatia he brought us back to it.

Copyright 2024 Tom Turcich. Excerpted by permission of Skyhorse Publishing Inc.

Read More on Monkeying Around in Nicaragua

———————

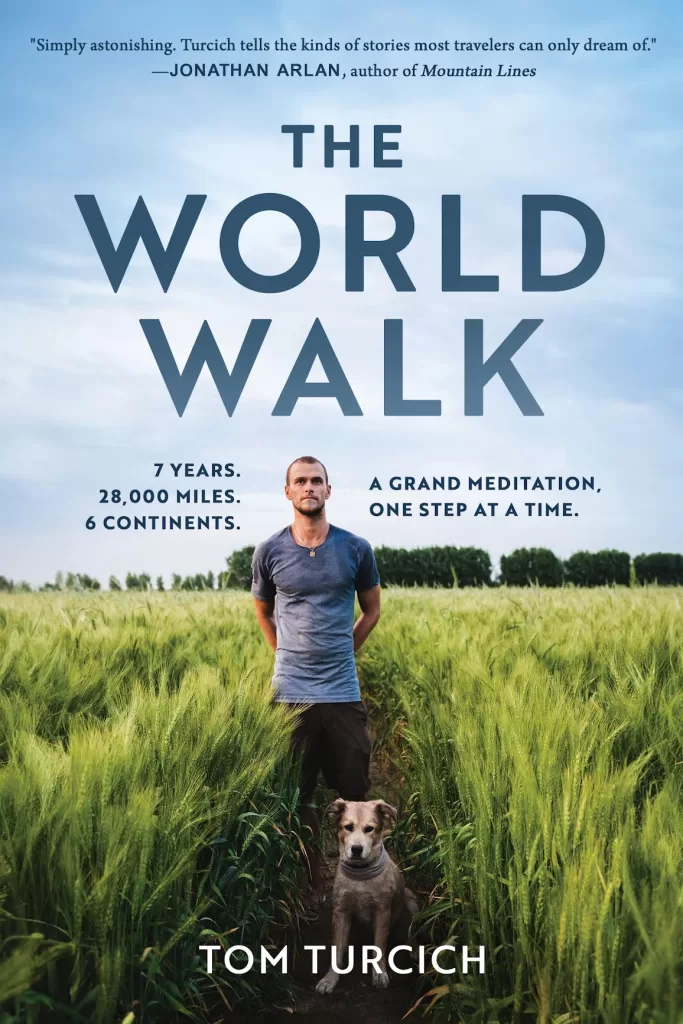

Thomas Turcich spent seven years walking around the world, which inspired his new book, The World Walk, from which this article is excerpted. Follow him on Instagram.